Can One Person Do It All? |

|

|

Objective: To obtain sufficient accurate data on an AOP sighting in order to constrain interpretations and eliminate most conventional and natural explanations. If an AOP is a conventional or military aircraft, enough visible and invisible data must be recorded to make a generic identification. However, without the help of automated equipment, one person will be incapable of operating all the instruments necessary to collect sufficient data for positive identification. Even with all his experience, skill at handling several instruments at the same time, and time spent in the field, Cornet was not able to positively identify one of the anomalous craft he photographed to the satisfaction of honest skeptics. One person can operate several pieces of equipment simultaneously, but there are obvious limitations unless most of the monitoring equipment has automated capability. For example, it is possible for one person to 1) operate a camera mounted on a tripod, 2) lock and unlock the tripod when changing the orientation of the camera, 3) turn an audio recorder on and off, 4) turn the light on a digital watch on to get the exact time, while 5) vocalizing the time so that it is recorded, 6) turning on a small penlight for 7) writing the time down in a notebook for each time exposure taken, 8) taking a compass reading for the camera orientation, and 9) writing that measurement down in the notebook. If a camcorder is used, a separate audio recorder is unnecessary, as is recording times if the camcorder records time in seconds. But is this necessary? Additional equipment which can be turned on and run continuously (automated) can also be used, such as a Proton Precession Magnetometer, airtraffic/weather scanner (placed near an audio recorder so that information will be recorded), and a Geiger-Mueller counter. The magnetometer can be configured to continuously store magnetic readings (with a time stamp for each measurement), but the Geiger-Mueller counter and ND-2RP do not have storage capability. An audio signal from the counter is required; the earphone or headset can be positioned or rigged next to the mic of an audio recorder or camcorder so that any radiation hits will be recorded during a close encounter.

1) Still shots provide very little information other than number, position, and colors of lights. 2) Time exposures also give you movement, flight behavior, strobe patterns, as well as changes in lights due either to changes in AOP orientation relative to the camera or to intentional turning of lights on or off. 3) Conventional aircraft normally fly in relatively straight paths unless banking or turning, or unless a stunt pilot is photographed doing aerobatics at night. And even then the path the lights make during aerobatics conforms to aerodynamic laws and predictable flight characteristics of the aircraft. 4) Any radical departure from normal flight paths or aircraft performance will be recorded by time exposures.

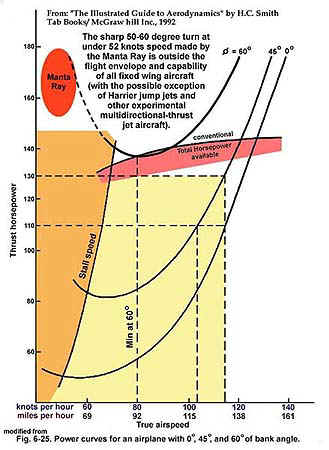

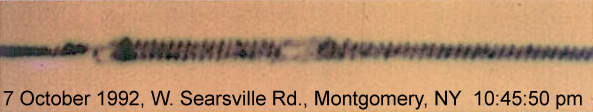

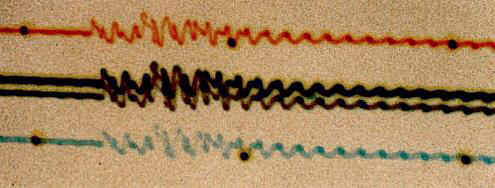

Sudden stops in midair, right angle turns, supersonic speeds at low altitude without sonic booms, aerobatic stunts such as flying backwards, changes in lighting pattern from one time exposure to another (not due to orientation), special lighting effects such as plasma plumes or trains of plasma orbs, tight loops, spirals, and offsets in motion produced by the lights (see above image) are just some of the abnormal patterns of light movement that have been recorded on time exposures. Such departures from normal flight increase the probability that an AOP is not a conventional or military aircraft or helicopter.

Actual Examples

5) Colors of lights and strobes will be faithfully recorded by time exposures. Blue lights are not allowed by FAA regulations, but have been recorded frequently for AOP. Sometimes AOP have navigation lights reversed from normal with the red wingtip light on the starboard (right) side rather than the port side. 6) Time exposures, if long enough in duration, will record tree outlines at night, which can be used for determining AOP altitude. Star patterns and trails will be recorded on clear nights, allowing confirmation of azimuth and inclination in the sky. Typically AOP fly below minimum aircraft altitudes regulated by the FAA when putting on performances. Caution Using Time Exposures It is important to experiment with your camera/tripod setup to determine how camera and/or tripod vibration will distort and alter the pattern of light movement. Typically vibration can occur when the shutter is opened,

but shutter vibration is uncommon. It is necessary to determine the length of time it takes for camera vibration to dampen on your setup, as well as what other kinds of disturbances to the camera/tripod system will produce artificial light movement on the film. Even a gentle tug on the shutter release cable or a soft bump to one of the tripod legs can cause significant vibration to appear in photographs. If the maximum time for vibrations to dampen is determined through experimentation (for example, taking time exposures of conventional aircraft at night), and a pattern of vibration for an AOP greatly exceeds that dampening time, you might be able to eliminate camera vibration as the cause. Pine Bush AOP were capable of producing various types of sine wave patterns and loops on time exposures.

Practice Makes Perfect Positioning or framing a set of lights in the camera viewfinder is one of the most important skills to be learned when setting up a shot. It is important to position the lights near one side of the frame, so that their movement will extend across the picture. As a set of aircraft lights gets closer to the camera, apparent speed will increase and the length of a time exposure will decrease to one or two seconds. It is important that no vibration be introduced to the camera/tripod system during fast camera setups. Most of the time awareness and deliberate movement of the camera, followed by locking the camera in position, will insure a stable shot. Strong steady wind can also set up a harmonic vibration in the tripod. Determining when to close the camera shutter is perhaps the most difficult challenge, because you cannot use through the lens viewfinders. Judging by position to a sighting point on top of the camera normally works, as does experience from practice. If times for the start and end of a time exposure are recorded, it is very important that the light trails not move off the picture before the shutter closes. It is better to end a shot early than to lose potentially valuable data for computing relative speeds and distances traveled. |

Field Procedure - Two or More People next.

Send mail to bcornet@monmouth.com with questions or comments about this web site.

Copyright © 2000 Sirius Onion Works.

This page was last edited 09/15/2005